Was London a nice and peaceful place in Victorian London? The short answer would seem to be, not at all. Oliver Twist has given a startling and lasting

impression of

what the streets of London were like at the beginning of Queen Victoria's reign,

with dens of thieves in the East End turning boys like Oliver into "fogle-hunters"

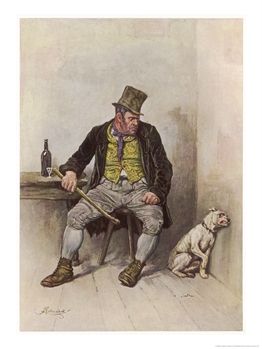

(see the opening of Chapter XI), burly housebreakers like Bill Sikes

impression of

what the streets of London were like at the beginning of Queen Victoria's reign,

with dens of thieves in the East End turning boys like Oliver into "fogle-hunters"

(see the opening of Chapter XI), burly housebreakers like Bill Sikes setting off

through the sleeping town to practice their skills in the leafy suburbs, and loose

women like Nancy being battered to death in dingy rooms or down dark alleys.

setting off

through the sleeping town to practice their skills in the leafy suburbs, and loose

women like Nancy being battered to death in dingy rooms or down dark alleys. A

generation later, Charles

Dickens (Jr) is hardly more reassuring than his father, advising householders to

lock up carefully and bring their mud-scrapers in at night if they happened to like

the patterns on them. Later in the reign too,

A

generation later, Charles

Dickens (Jr) is hardly more reassuring than his father, advising householders to

lock up carefully and bring their mud-scrapers in at night if they happened to like

the patterns on them. Later in the reign too, social problem novels like George Gissing's

The Nether World (1889) were still painting a lurid

picture of slums in the East End, whose denizens grew as "vile" as their

surroundings (Gissing Ch VIII),

social problem novels like George Gissing's

The Nether World (1889) were still painting a lurid

picture of slums in the East End, whose denizens grew as "vile" as their

surroundings (Gissing Ch VIII), and were, of course, only a stone's throw from the

City and (worse!) only a couple of stone's throws away from the monied residents of

the West End

and were, of course, only a stone's throw from the

City and (worse!) only a couple of stone's throws away from the monied residents of

the West End

During the 1840s, London

became established as the capital of the British Empire, the centre of

international trade and the hub of a vast world market. As it became

part of the rapidly expanding city,  Holloway Road teemed with places of

consumption, pleasure and escape – department stores, music halls,

theatres and picture palaces.

Holloway Road teemed with places of

consumption, pleasure and escape – department stores, music halls,

theatres and picture palaces.

From 1840 onwards, small shops opened for business, particularly on the east side of Holloway Road, with an abundance of goods displayed behind the newly fashionable plate glass. The typical distinctive Victorian shop had timber panelled shopfront, with perhaps an awning, and a sign above giving the name of the proprietor.

By the end of the nineteenth century, Holloway Road was in its heyday. It was a flourishing urban centre with famous department stores such as James Selby (opening in 1896 as Milliners and General Draper), Thomas Usher (nos. 376 – 380), and Jones Brothers (nos. 348 –366). A landmark was Beale’s Restaurant, an ornate and imposing neo Gothic five

storey building built on the corner of Tollington Road in 1869. In stark

contrast to the bright department stores, bargaining and buying and

selling were carried out on the street: match sellers, shoe blacks,

milkmen, drinks sellers, prostitutes and beggars.Crime begins with wealth and thus follows it around,

an ornate and imposing neo Gothic five

storey building built on the corner of Tollington Road in 1869. In stark

contrast to the bright department stores, bargaining and buying and

selling were carried out on the street: match sellers, shoe blacks,

milkmen, drinks sellers, prostitutes and beggars.Crime begins with wealth and thus follows it around, The destruction of Beale’s in 1969, and the arrival of Sainsbury’s (now Argos) in 1970, heralded the arrival of the supermarket in Holloway Road. In the late 1980s, the Nag’s Head Shopping Arcade was built.

The destruction of Beale’s in 1969, and the arrival of Sainsbury’s (now Argos) in 1970, heralded the arrival of the supermarket in Holloway Road. In the late 1980s, the Nag’s Head Shopping Arcade was built. In 1990, Jones Brothers closed, in the face of public outcry, to be replaced by a branch of Waitrose. Other supermarkets have recently appeared near Archway and Highbury Corner. Today, Holloway Road is a mix of the standardised and the particular. Alongside the ubiquitous names of the British high street, Selby’s department store thrives at the Nag’s Head.

In 1990, Jones Brothers closed, in the face of public outcry, to be replaced by a branch of Waitrose. Other supermarkets have recently appeared near Archway and Highbury Corner. Today, Holloway Road is a mix of the standardised and the particular. Alongside the ubiquitous names of the British high street, Selby’s department store thrives at the Nag’s Head.

Stretching from Highbury Corner to Eden Grove, the Holloway Road Conservation Grant Scheme has funded improvements to nineteenth century shop fronts as a means of encouraging regeneration and economic vitality.

Stretching from Highbury Corner to Eden Grove, the Holloway Road Conservation Grant Scheme has funded improvements to nineteenth century shop fronts as a means of encouraging regeneration and economic vitality.

Transformed from the genteel, well-to-do shopping street of the 1890s, frequented by Mr Pooter, Holloway Road today is a vibrant inner London high road, where the shops provide the everyday necessities, alongside the weird, the exotic, the down at heel, and the many hidden treasures.

The character of the London criminal scene in the years just before the First World War is revealed in the life of Arthur Harding, whose memories were published by the historian Raphael Samuel. Harding described his native area of Whitechapel at the turn of the century:

The sensational murder stories in the Victorian era sold newspapers and crime fiction in a way that had never been seen before, stories which continue to fascinate us today.

Holloway Road teemed with places of

consumption, pleasure and escape – department stores, music halls,

theatres and picture palaces.

Holloway Road teemed with places of

consumption, pleasure and escape – department stores, music halls,

theatres and picture palaces.

From 1840 onwards, small shops opened for business, particularly on the east side of Holloway Road, with an abundance of goods displayed behind the newly fashionable plate glass. The typical distinctive Victorian shop had timber panelled shopfront, with perhaps an awning, and a sign above giving the name of the proprietor.

By the end of the nineteenth century, Holloway Road was in its heyday. It was a flourishing urban centre with famous department stores such as James Selby (opening in 1896 as Milliners and General Draper), Thomas Usher (nos. 376 – 380), and Jones Brothers (nos. 348 –366). A landmark was Beale’s Restaurant,

an ornate and imposing neo Gothic five

storey building built on the corner of Tollington Road in 1869. In stark

contrast to the bright department stores, bargaining and buying and

selling were carried out on the street: match sellers, shoe blacks,

milkmen, drinks sellers, prostitutes and beggars.Crime begins with wealth and thus follows it around,

an ornate and imposing neo Gothic five

storey building built on the corner of Tollington Road in 1869. In stark

contrast to the bright department stores, bargaining and buying and

selling were carried out on the street: match sellers, shoe blacks,

milkmen, drinks sellers, prostitutes and beggars.Crime begins with wealth and thus follows it around, The destruction of Beale’s in 1969, and the arrival of Sainsbury’s (now Argos) in 1970, heralded the arrival of the supermarket in Holloway Road. In the late 1980s, the Nag’s Head Shopping Arcade was built.

The destruction of Beale’s in 1969, and the arrival of Sainsbury’s (now Argos) in 1970, heralded the arrival of the supermarket in Holloway Road. In the late 1980s, the Nag’s Head Shopping Arcade was built. In 1990, Jones Brothers closed, in the face of public outcry, to be replaced by a branch of Waitrose. Other supermarkets have recently appeared near Archway and Highbury Corner. Today, Holloway Road is a mix of the standardised and the particular. Alongside the ubiquitous names of the British high street, Selby’s department store thrives at the Nag’s Head.

In 1990, Jones Brothers closed, in the face of public outcry, to be replaced by a branch of Waitrose. Other supermarkets have recently appeared near Archway and Highbury Corner. Today, Holloway Road is a mix of the standardised and the particular. Alongside the ubiquitous names of the British high street, Selby’s department store thrives at the Nag’s Head. Stretching from Highbury Corner to Eden Grove, the Holloway Road Conservation Grant Scheme has funded improvements to nineteenth century shop fronts as a means of encouraging regeneration and economic vitality.

Stretching from Highbury Corner to Eden Grove, the Holloway Road Conservation Grant Scheme has funded improvements to nineteenth century shop fronts as a means of encouraging regeneration and economic vitality.

Transformed from the genteel, well-to-do shopping street of the 1890s, frequented by Mr Pooter, Holloway Road today is a vibrant inner London high road, where the shops provide the everyday necessities, alongside the weird, the exotic, the down at heel, and the many hidden treasures.

In the 1890s it appears that in all 73,240 persons were taken into custody, of whom 45,941 were males, and 27,209 females; 18,000 of the apprehensions were on account of drunkenness, 8160 for unlawful possession of goods, 7021 for simple larceny, 6763 for common assaults, 2194 for assaults on the police; 4303 women were taken into custody as prostitutes. (qtd. in Jackson 63)

But there much to suggest that this was only the tip of the iceberg. The problem was that crimes often went unrecorded, let alone solved. In the early years, people had little confidence in their new police force (See Bloy, "Metropolitan Police Force"). Peel had organised London into seventeen police regions, and insisted "that merit, not patronage, must from the outset govern the  recruitment of his new police officers" (Hurd 104); but the first intakes of "bobbies" left much to be desired. Many were quickly dismissed, "mainly for drunkenness on duty" (Richardson 436).

recruitment of his new police officers" (Hurd 104); but the first intakes of "bobbies" left much to be desired. Many were quickly dismissed, "mainly for drunkenness on duty" (Richardson 436).  Victims of thefts, muggings and so on knew it was useless to complain to them. "We never tell the police," said one tradesman in the Gray's Inn Road area, "it's no good" (qtd. in White 342).

Victims of thefts, muggings and so on knew it was useless to complain to them. "We never tell the police," said one tradesman in the Gray's Inn Road area, "it's no good" (qtd. in White 342).  Moreover, some were intimidated by their assailants, or embarrassed by the circumstances of the crime — their own drunkenness at that time, for example, or involvement with prostitutes. For their part, the police, all too aware of their own deficiencies, kept a separate tally for suspected crimes, which did not need to be included in the figures of known crimes (White 343).

Moreover, some were intimidated by their assailants, or embarrassed by the circumstances of the crime — their own drunkenness at that time, for example, or involvement with prostitutes. For their part, the police, all too aware of their own deficiencies, kept a separate tally for suspected crimes, which did not need to be included in the figures of known crimes (White 343).  Even cases of murder (including infanticide) could escape from the records when coroners, dependent on limited forensic evidence, were forced to return open verdicts. There were some humane judges, too, who engineered acquittals for minor offences then still punishable by transportation or even death (Parker 439). Finally, record-keeping itself had yet to come of age. The precursor of the Criminal Records Office was set up only in 1869.

Even cases of murder (including infanticide) could escape from the records when coroners, dependent on limited forensic evidence, were forced to return open verdicts. There were some humane judges, too, who engineered acquittals for minor offences then still punishable by transportation or even death (Parker 439). Finally, record-keeping itself had yet to come of age. The precursor of the Criminal Records Office was set up only in 1869.  In all likelihood, then, "peace-loving citizens" tried to keep their wits about them at all times.Leaving aside drunkenness, theft was rampant. While children might pickpocket and steal from barrows on the streets, women might engage in shoplifting, and, as for London's sly con men, cheats, "magsmen" or "sharpers," they were notorious.

In all likelihood, then, "peace-loving citizens" tried to keep their wits about them at all times.Leaving aside drunkenness, theft was rampant. While children might pickpocket and steal from barrows on the streets, women might engage in shoplifting, and, as for London's sly con men, cheats, "magsmen" or "sharpers," they were notorious.  So were the housebreakers working in teams, and slipping into homes and shops and warehouses. Mugging, with its associated violence, was rife. A hanky dipped in chloroform might be used to subdue someone before robbing him, or a man's hat might be tipped over his face to facilitate the crime (this was called "bonneting").

So were the housebreakers working in teams, and slipping into homes and shops and warehouses. Mugging, with its associated violence, was rife. A hanky dipped in chloroform might be used to subdue someone before robbing him, or a man's hat might be tipped over his face to facilitate the crime (this was called "bonneting").  Another ruse was to lure men down to the riverside by using prostitutes as decoys. The dupes would then be beaten up and robbed out of sight of passers-by. Violence could, of course, easily extend to murder.

Another ruse was to lure men down to the riverside by using prostitutes as decoys. The dupes would then be beaten up and robbed out of sight of passers-by. Violence could, of course, easily extend to murder. Prostitutes themselves ran huge risks. No one knows how many of them were strangled or stabbed or butchered (Jack the Ripper was far from the only villain, and Dickens's Nancy must be mourned for many a pitiful "lost woman").

Prostitutes themselves ran huge risks. No one knows how many of them were strangled or stabbed or butchered (Jack the Ripper was far from the only villain, and Dickens's Nancy must be mourned for many a pitiful "lost woman"). No respectable woman would have ventured forth after dark at all, if she had any choice in the matter. Even if a policeman appeared on the crime scene, he might be driven off by having nitric acid thrown in his face.

No respectable woman would have ventured forth after dark at all, if she had any choice in the matter. Even if a policeman appeared on the crime scene, he might be driven off by having nitric acid thrown in his face. The helpless were at special risk. Well-turned-out children might be waylaid, dragged down an alley, and stripped of their finery, or pet dogs kidnapped for ransom or simply filched for their skins. Around mid-century, and again in 1862, "garrotting" or half-strangling unwary pedestrians from behind while accomplices stripped them of their valuables, caused great waves of panic (White 337).

The helpless were at special risk. Well-turned-out children might be waylaid, dragged down an alley, and stripped of their finery, or pet dogs kidnapped for ransom or simply filched for their skins. Around mid-century, and again in 1862, "garrotting" or half-strangling unwary pedestrians from behind while accomplices stripped them of their valuables, caused great waves of panic (White 337).  There were big-time criminals as well as gangs of street hooligans. In a new version of highway robbery, for instance, bankers' consignments might be snatched in transit. There was also a surge in gun crime in the 1880s, and hardened burglars "increasingly went armed"Probably the riskiest places for theft and pickpocketing were in the open markets of the East End (Whitechapel, the haunt of Jack the Ripper in 1888,

There were big-time criminals as well as gangs of street hooligans. In a new version of highway robbery, for instance, bankers' consignments might be snatched in transit. There was also a surge in gun crime in the 1880s, and hardened burglars "increasingly went armed"Probably the riskiest places for theft and pickpocketing were in the open markets of the East End (Whitechapel, the haunt of Jack the Ripper in 1888,  often crops up in this context too), the insalubrious areas of south London, and crowded railway stations. But it was risky to be anywhere where many people gathered or, alternatively, where there was no one else around. Lee Jackson's Dictionary of Victorian London includes a letter to The Times from 1850, recording a mugging by Regent's Park. The assailants were two fashionably-dressed young men who started by chatting to their victim quite innocuously about the weather, and later eluded a policemen who thought them to be "gents" larking around after a night on the town (174). Liza Picard in Victorian London gives the case of an MP "walking along Pall Mall in broad daylight one day in 1862, when two men attacked and 'garrotted' him, one beating him while the other stole his watch"; Picard quotes a French visitor who wrote in 1866: "Crime is developing itself into a mania ... London has ceased to be a city which one can traverse at night with mind at rest and the hands in the pockets" (329). As Charles Dickens Jr's advice suggests, home wasn't much of a refuge either, with large rises in housebreaking recorded towards the end of the century

often crops up in this context too), the insalubrious areas of south London, and crowded railway stations. But it was risky to be anywhere where many people gathered or, alternatively, where there was no one else around. Lee Jackson's Dictionary of Victorian London includes a letter to The Times from 1850, recording a mugging by Regent's Park. The assailants were two fashionably-dressed young men who started by chatting to their victim quite innocuously about the weather, and later eluded a policemen who thought them to be "gents" larking around after a night on the town (174). Liza Picard in Victorian London gives the case of an MP "walking along Pall Mall in broad daylight one day in 1862, when two men attacked and 'garrotted' him, one beating him while the other stole his watch"; Picard quotes a French visitor who wrote in 1866: "Crime is developing itself into a mania ... London has ceased to be a city which one can traverse at night with mind at rest and the hands in the pockets" (329). As Charles Dickens Jr's advice suggests, home wasn't much of a refuge either, with large rises in housebreaking recorded towards the end of the century (White 335). There was general panic in the capital on more than one occasion, the worst being on "Bloody Sunday" in November 1887 when hordes of East Enders, the dreaded "King Mob," were denied access to Trafalgar Square for a socialist demonstration. "[O]ne feels as if one might meet

(White 335). There was general panic in the capital on more than one occasion, the worst being on "Bloody Sunday" in November 1887 when hordes of East Enders, the dreaded "King Mob," were denied access to Trafalgar Square for a socialist demonstration. "[O]ne feels as if one might meet  violence any where," wrote the social reformer Octavia Hill in 1886 (qtd. in Walkowitz 29).London did get safer on the whole. The Metropolitan Police Force grew larger and more efficient. Such was the show of force that at Trafalgar Square, for example, hundreds of workers were injured, and three people died. This upset some people (see Cody, "Morris's Socialism"), but generally speaking "[b]y the 1880s the police were more popular than they had been in the 1830s" (Ford and Harrison 239). The policeman's whistle, replacing the original rattle, was usually enough to scatter the common class of scoundrels. The use of telegraphs, photography and (right at the end of the period) fingerprinting all helped to make life riskier for habitual offenders. But perhaps more important than improved policing were improved social conditions, due in no small part to the alerting of the public to the roots of crime — most forcibly by Dickens. The clearing of "rookeries" or slums by new roads like New Oxford Street (which cut across the rookery at St Giles), the charitable efforts of the great philanthropists like George Peabody and Angela Burdett-Coutts, and the introduction of compulsory elementary education in 1870, all had an impact.

violence any where," wrote the social reformer Octavia Hill in 1886 (qtd. in Walkowitz 29).London did get safer on the whole. The Metropolitan Police Force grew larger and more efficient. Such was the show of force that at Trafalgar Square, for example, hundreds of workers were injured, and three people died. This upset some people (see Cody, "Morris's Socialism"), but generally speaking "[b]y the 1880s the police were more popular than they had been in the 1830s" (Ford and Harrison 239). The policeman's whistle, replacing the original rattle, was usually enough to scatter the common class of scoundrels. The use of telegraphs, photography and (right at the end of the period) fingerprinting all helped to make life riskier for habitual offenders. But perhaps more important than improved policing were improved social conditions, due in no small part to the alerting of the public to the roots of crime — most forcibly by Dickens. The clearing of "rookeries" or slums by new roads like New Oxford Street (which cut across the rookery at St Giles), the charitable efforts of the great philanthropists like George Peabody and Angela Burdett-Coutts, and the introduction of compulsory elementary education in 1870, all had an impact. .jpeg) For example, the number of convicts under the age of seventeen declined markedly during the 1870s, though less rapidly thereafter (Ford and Harrison 240). Ritchie had pointed out that "[t]he period of life most prolific of crime is that between the 20th and 25th years" (qtd. in Jackson 63), so the provision of educational and recreational opportunities for young men must have helped too. Charles Booth, the well-known social investigator, recorded an interview with Louis Vedy of the Y Police Division, Kentish Town, on 2 December 1897: "On the whole he said crime was decreasing especially crime with violence. People are less brutal than they used to be. Change due he thinks to better teaching. Even the reformatories turn out a large proportion who become respectable citizens." There were still what Walter Besant calls "certain street companies" (174), in other words, gangs of hooligans looking for trouble. Perhaps these will always prowl our urban jungles. And mugging, knifing and so on would never be eliminated. Still, on the whole, social commentators agree that "London was a more law-abiding city in the third and fourth quarters of the [nineteenth] century than before and a less brutal and savage place as well" (White 349).

For example, the number of convicts under the age of seventeen declined markedly during the 1870s, though less rapidly thereafter (Ford and Harrison 240). Ritchie had pointed out that "[t]he period of life most prolific of crime is that between the 20th and 25th years" (qtd. in Jackson 63), so the provision of educational and recreational opportunities for young men must have helped too. Charles Booth, the well-known social investigator, recorded an interview with Louis Vedy of the Y Police Division, Kentish Town, on 2 December 1897: "On the whole he said crime was decreasing especially crime with violence. People are less brutal than they used to be. Change due he thinks to better teaching. Even the reformatories turn out a large proportion who become respectable citizens." There were still what Walter Besant calls "certain street companies" (174), in other words, gangs of hooligans looking for trouble. Perhaps these will always prowl our urban jungles. And mugging, knifing and so on would never be eliminated. Still, on the whole, social commentators agree that "London was a more law-abiding city in the third and fourth quarters of the [nineteenth] century than before and a less brutal and savage place as well" (White 349).

recruitment of his new police officers" (Hurd 104); but the first intakes of "bobbies" left much to be desired. Many were quickly dismissed, "mainly for drunkenness on duty" (Richardson 436).

recruitment of his new police officers" (Hurd 104); but the first intakes of "bobbies" left much to be desired. Many were quickly dismissed, "mainly for drunkenness on duty" (Richardson 436).  Victims of thefts, muggings and so on knew it was useless to complain to them. "We never tell the police," said one tradesman in the Gray's Inn Road area, "it's no good" (qtd. in White 342).

Victims of thefts, muggings and so on knew it was useless to complain to them. "We never tell the police," said one tradesman in the Gray's Inn Road area, "it's no good" (qtd. in White 342).  Moreover, some were intimidated by their assailants, or embarrassed by the circumstances of the crime — their own drunkenness at that time, for example, or involvement with prostitutes. For their part, the police, all too aware of their own deficiencies, kept a separate tally for suspected crimes, which did not need to be included in the figures of known crimes (White 343).

Moreover, some were intimidated by their assailants, or embarrassed by the circumstances of the crime — their own drunkenness at that time, for example, or involvement with prostitutes. For their part, the police, all too aware of their own deficiencies, kept a separate tally for suspected crimes, which did not need to be included in the figures of known crimes (White 343).  Even cases of murder (including infanticide) could escape from the records when coroners, dependent on limited forensic evidence, were forced to return open verdicts. There were some humane judges, too, who engineered acquittals for minor offences then still punishable by transportation or even death (Parker 439). Finally, record-keeping itself had yet to come of age. The precursor of the Criminal Records Office was set up only in 1869.

Even cases of murder (including infanticide) could escape from the records when coroners, dependent on limited forensic evidence, were forced to return open verdicts. There were some humane judges, too, who engineered acquittals for minor offences then still punishable by transportation or even death (Parker 439). Finally, record-keeping itself had yet to come of age. The precursor of the Criminal Records Office was set up only in 1869.  In all likelihood, then, "peace-loving citizens" tried to keep their wits about them at all times.Leaving aside drunkenness, theft was rampant. While children might pickpocket and steal from barrows on the streets, women might engage in shoplifting, and, as for London's sly con men, cheats, "magsmen" or "sharpers," they were notorious.

In all likelihood, then, "peace-loving citizens" tried to keep their wits about them at all times.Leaving aside drunkenness, theft was rampant. While children might pickpocket and steal from barrows on the streets, women might engage in shoplifting, and, as for London's sly con men, cheats, "magsmen" or "sharpers," they were notorious.  So were the housebreakers working in teams, and slipping into homes and shops and warehouses. Mugging, with its associated violence, was rife. A hanky dipped in chloroform might be used to subdue someone before robbing him, or a man's hat might be tipped over his face to facilitate the crime (this was called "bonneting").

So were the housebreakers working in teams, and slipping into homes and shops and warehouses. Mugging, with its associated violence, was rife. A hanky dipped in chloroform might be used to subdue someone before robbing him, or a man's hat might be tipped over his face to facilitate the crime (this was called "bonneting").  Another ruse was to lure men down to the riverside by using prostitutes as decoys. The dupes would then be beaten up and robbed out of sight of passers-by. Violence could, of course, easily extend to murder.

Another ruse was to lure men down to the riverside by using prostitutes as decoys. The dupes would then be beaten up and robbed out of sight of passers-by. Violence could, of course, easily extend to murder. Prostitutes themselves ran huge risks. No one knows how many of them were strangled or stabbed or butchered (Jack the Ripper was far from the only villain, and Dickens's Nancy must be mourned for many a pitiful "lost woman").

Prostitutes themselves ran huge risks. No one knows how many of them were strangled or stabbed or butchered (Jack the Ripper was far from the only villain, and Dickens's Nancy must be mourned for many a pitiful "lost woman"). No respectable woman would have ventured forth after dark at all, if she had any choice in the matter. Even if a policeman appeared on the crime scene, he might be driven off by having nitric acid thrown in his face.

No respectable woman would have ventured forth after dark at all, if she had any choice in the matter. Even if a policeman appeared on the crime scene, he might be driven off by having nitric acid thrown in his face. The helpless were at special risk. Well-turned-out children might be waylaid, dragged down an alley, and stripped of their finery, or pet dogs kidnapped for ransom or simply filched for their skins. Around mid-century, and again in 1862, "garrotting" or half-strangling unwary pedestrians from behind while accomplices stripped them of their valuables, caused great waves of panic (White 337).

The helpless were at special risk. Well-turned-out children might be waylaid, dragged down an alley, and stripped of their finery, or pet dogs kidnapped for ransom or simply filched for their skins. Around mid-century, and again in 1862, "garrotting" or half-strangling unwary pedestrians from behind while accomplices stripped them of their valuables, caused great waves of panic (White 337).  There were big-time criminals as well as gangs of street hooligans. In a new version of highway robbery, for instance, bankers' consignments might be snatched in transit. There was also a surge in gun crime in the 1880s, and hardened burglars "increasingly went armed"Probably the riskiest places for theft and pickpocketing were in the open markets of the East End (Whitechapel, the haunt of Jack the Ripper in 1888,

There were big-time criminals as well as gangs of street hooligans. In a new version of highway robbery, for instance, bankers' consignments might be snatched in transit. There was also a surge in gun crime in the 1880s, and hardened burglars "increasingly went armed"Probably the riskiest places for theft and pickpocketing were in the open markets of the East End (Whitechapel, the haunt of Jack the Ripper in 1888,  often crops up in this context too), the insalubrious areas of south London, and crowded railway stations. But it was risky to be anywhere where many people gathered or, alternatively, where there was no one else around. Lee Jackson's Dictionary of Victorian London includes a letter to The Times from 1850, recording a mugging by Regent's Park. The assailants were two fashionably-dressed young men who started by chatting to their victim quite innocuously about the weather, and later eluded a policemen who thought them to be "gents" larking around after a night on the town (174). Liza Picard in Victorian London gives the case of an MP "walking along Pall Mall in broad daylight one day in 1862, when two men attacked and 'garrotted' him, one beating him while the other stole his watch"; Picard quotes a French visitor who wrote in 1866: "Crime is developing itself into a mania ... London has ceased to be a city which one can traverse at night with mind at rest and the hands in the pockets" (329). As Charles Dickens Jr's advice suggests, home wasn't much of a refuge either, with large rises in housebreaking recorded towards the end of the century

often crops up in this context too), the insalubrious areas of south London, and crowded railway stations. But it was risky to be anywhere where many people gathered or, alternatively, where there was no one else around. Lee Jackson's Dictionary of Victorian London includes a letter to The Times from 1850, recording a mugging by Regent's Park. The assailants were two fashionably-dressed young men who started by chatting to their victim quite innocuously about the weather, and later eluded a policemen who thought them to be "gents" larking around after a night on the town (174). Liza Picard in Victorian London gives the case of an MP "walking along Pall Mall in broad daylight one day in 1862, when two men attacked and 'garrotted' him, one beating him while the other stole his watch"; Picard quotes a French visitor who wrote in 1866: "Crime is developing itself into a mania ... London has ceased to be a city which one can traverse at night with mind at rest and the hands in the pockets" (329). As Charles Dickens Jr's advice suggests, home wasn't much of a refuge either, with large rises in housebreaking recorded towards the end of the century (White 335). There was general panic in the capital on more than one occasion, the worst being on "Bloody Sunday" in November 1887 when hordes of East Enders, the dreaded "King Mob," were denied access to Trafalgar Square for a socialist demonstration. "[O]ne feels as if one might meet

(White 335). There was general panic in the capital on more than one occasion, the worst being on "Bloody Sunday" in November 1887 when hordes of East Enders, the dreaded "King Mob," were denied access to Trafalgar Square for a socialist demonstration. "[O]ne feels as if one might meet  violence any where," wrote the social reformer Octavia Hill in 1886 (qtd. in Walkowitz 29).London did get safer on the whole. The Metropolitan Police Force grew larger and more efficient. Such was the show of force that at Trafalgar Square, for example, hundreds of workers were injured, and three people died. This upset some people (see Cody, "Morris's Socialism"), but generally speaking "[b]y the 1880s the police were more popular than they had been in the 1830s" (Ford and Harrison 239). The policeman's whistle, replacing the original rattle, was usually enough to scatter the common class of scoundrels. The use of telegraphs, photography and (right at the end of the period) fingerprinting all helped to make life riskier for habitual offenders. But perhaps more important than improved policing were improved social conditions, due in no small part to the alerting of the public to the roots of crime — most forcibly by Dickens. The clearing of "rookeries" or slums by new roads like New Oxford Street (which cut across the rookery at St Giles), the charitable efforts of the great philanthropists like George Peabody and Angela Burdett-Coutts, and the introduction of compulsory elementary education in 1870, all had an impact.

violence any where," wrote the social reformer Octavia Hill in 1886 (qtd. in Walkowitz 29).London did get safer on the whole. The Metropolitan Police Force grew larger and more efficient. Such was the show of force that at Trafalgar Square, for example, hundreds of workers were injured, and three people died. This upset some people (see Cody, "Morris's Socialism"), but generally speaking "[b]y the 1880s the police were more popular than they had been in the 1830s" (Ford and Harrison 239). The policeman's whistle, replacing the original rattle, was usually enough to scatter the common class of scoundrels. The use of telegraphs, photography and (right at the end of the period) fingerprinting all helped to make life riskier for habitual offenders. But perhaps more important than improved policing were improved social conditions, due in no small part to the alerting of the public to the roots of crime — most forcibly by Dickens. The clearing of "rookeries" or slums by new roads like New Oxford Street (which cut across the rookery at St Giles), the charitable efforts of the great philanthropists like George Peabody and Angela Burdett-Coutts, and the introduction of compulsory elementary education in 1870, all had an impact. .jpeg) For example, the number of convicts under the age of seventeen declined markedly during the 1870s, though less rapidly thereafter (Ford and Harrison 240). Ritchie had pointed out that "[t]he period of life most prolific of crime is that between the 20th and 25th years" (qtd. in Jackson 63), so the provision of educational and recreational opportunities for young men must have helped too. Charles Booth, the well-known social investigator, recorded an interview with Louis Vedy of the Y Police Division, Kentish Town, on 2 December 1897: "On the whole he said crime was decreasing especially crime with violence. People are less brutal than they used to be. Change due he thinks to better teaching. Even the reformatories turn out a large proportion who become respectable citizens." There were still what Walter Besant calls "certain street companies" (174), in other words, gangs of hooligans looking for trouble. Perhaps these will always prowl our urban jungles. And mugging, knifing and so on would never be eliminated. Still, on the whole, social commentators agree that "London was a more law-abiding city in the third and fourth quarters of the [nineteenth] century than before and a less brutal and savage place as well" (White 349).

For example, the number of convicts under the age of seventeen declined markedly during the 1870s, though less rapidly thereafter (Ford and Harrison 240). Ritchie had pointed out that "[t]he period of life most prolific of crime is that between the 20th and 25th years" (qtd. in Jackson 63), so the provision of educational and recreational opportunities for young men must have helped too. Charles Booth, the well-known social investigator, recorded an interview with Louis Vedy of the Y Police Division, Kentish Town, on 2 December 1897: "On the whole he said crime was decreasing especially crime with violence. People are less brutal than they used to be. Change due he thinks to better teaching. Even the reformatories turn out a large proportion who become respectable citizens." There were still what Walter Besant calls "certain street companies" (174), in other words, gangs of hooligans looking for trouble. Perhaps these will always prowl our urban jungles. And mugging, knifing and so on would never be eliminated. Still, on the whole, social commentators agree that "London was a more law-abiding city in the third and fourth quarters of the [nineteenth] century than before and a less brutal and savage place as well" (White 349).

Gender-related crimes, like domestic violence and infanticide, were still liable to go unreported. Account for this in the context of women's issues in general. (It would be useful to take a look at Timothy Farrell's "Separate Spheres: Victorian Constructions of Gender in Great Expectations.")

Dickens is the most important author to have dealt with this subject. As well as Oliver Twist and Great Expectations, see particularly Bleak House; also Philip Collins's Dickens and Crime, now in its 3rd ed. (Palgrave Macmillan, 1995). This has a whole chapter on the police, for instance. Why was Dickens charged with sentimentalising or (like William Harrison Ainsworth) romanticising the criminal? Are the charges fair?

Despite evident improvements, the perception of crime in the East End seems to have grown rather than diminished during this period. What factors fuelled people's fears? (As source material, look up some of the other contemporary books about the area, such as John Hollingshead's Ragged London in 1861 [1861], Andrew Mearns's The Bitter Cry of Outcast London [1883], Margaret Harkness's In Darkest London [1889] and Walter Besant's East London [1899]. Only a little later, Jack London penetrated its unhallowed depths, recording the experience in The People of the Abyss [1903], available here.)

How does the problem of crime in Victorian London relate to today's society? Note that only recently (25 January 2008) many London newspapers ran reports on "Operation Caddy," the appropriately Dickensian code-name for police raids on suspected "modern Fagins," who were thought to be training child slaves for pickpocketing and so on.

London, especially areas like the East End, contained criminal areas from earliest times. Some of the old 'rookeries' such a Clerkenwell had been hideouts for generations of professional burglars, pickpockets, forgers and the like. But was there anything approaching the continuous activity that we associate with organised crime, and what was its relationship with the local communities from which its members came?

The character of the London criminal scene in the years just before the First World War is revealed in the life of Arthur Harding, whose memories were published by the historian Raphael Samuel. Harding described his native area of Whitechapel at the turn of the century:

"Edward Emmanuel had a group of Jewish terrors. There was Jackie Berman. He told a pack of lies against me in the vendetta case - he had me put away… Bobby Levy - he lived down Chingford way - and his brother Moey. Bobby Nark - he was a good fighting chap. In later years all the Jewish terrors worked with the Italian mob on the race course… The Narks were a famous Jewish family from out of Aldgate. Bobby was a fine big fellow though he wasn't very brainy. His team used to hang out in a pub at Aldgate on the corner of Petticoat Lane. I've seen him smash a bloke's hat over his face and knock his beer over. He belonged to the Darby Sabini gang - that was made up of Jewish chaps and Italian chaps. He married an English lady - stone rich - they said she was worth thousands and thousands of pounds. He's dead and gone now. (Samuel 1981: 133-4)In other words the East End of London was a bit like American cities only on a smaller scale - different ethnic groups had their local gangs, sometimes they worked together and sometimes they fought each other. No group was powerful enough to dominate the scene entirely.

The sensational murder stories in the Victorian era sold newspapers and crime fiction in a way that had never been seen before, stories which continue to fascinate us today.

On a summer's evening in July 1864, a banker named Thomas Briggs was attacked in the first class compartment of a Hackney-bound train. Blood was found in the carriage and a few hours later Briggs was found near the tracks, seriously injured. He died soon after from his injuries.

It was the first murder on a railway and the story shocked and intrigued the nation. The newspapers followed it in great detail. An editorial in The Daily Telegraph reported:

"As news of the murder spread a feverish fear emerged. It was said that no-one knew when they opened a carriage door that they might not find blood on the cushion, that not a parent would entrust his daughter to the train without a horrid anxiety. That not a traveller took his seat without feeling how he runs his chance.Stories like the railway murder gripped the nation.

People have always frightened and bored me consequently I have been within my own shell and have not accomplished anything materially.

"

People have always frightened and bored me consequently I have been within my own shell and have not accomplished anything materially.

"

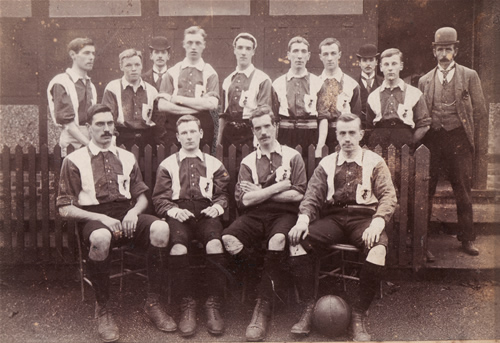

in central London of the FA. He wrote the first set of rules of true modern football at his house in Barnes.

in central London of the FA. He wrote the first set of rules of true modern football at his house in Barnes.  The modern passing game was invented in London in the early 1870s by the Royal Engineers A.F.C..

The modern passing game was invented in London in the early 1870s by the Royal Engineers A.F.C.. on 26 October 1863, there were no universally accepted rules for the playing of the game of football. The founder members present at the first meeting were Barnes, Civil Service

on 26 October 1863, there were no universally accepted rules for the playing of the game of football. The founder members present at the first meeting were Barnes, Civil Service